Functional Shape and Three-Dimensional Trademarks: Four “Twin” Judgments of the EU General Court on the Rubik’s Cube

By four judgments delivered on the same day – Cases T-1170/23, T-1171/23, T-1172/23 and T-1173/23 – the General Court of the European Union definitively confirmed the invalidity of four EU three-dimensional trademarks, all owned by Spin Master Toys UK Ltd and all relating to variants of the well-known cube-shaped puzzle.

These decisions are substantially overlapping, both in their reasoning and in the solutions adopted, and may be read as a single coherent intervention on the issue of functional shape within EU trademark law, a topic we have previously addressed, for example, here.

The judgments concern, respectively, EU trademark No. 9975681 (Case T-1170/23), EU trade mark No. 5696232 (Case T-1171/23), EU trademark No. 9976135 (Case T-1172/23) and EU trademark No. 9976788 (Case T-1173/23), reproduced below.

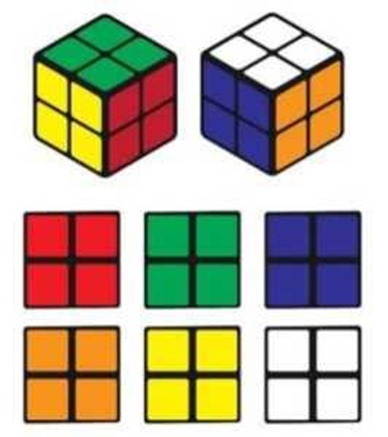

EU Trademark No. 9975681

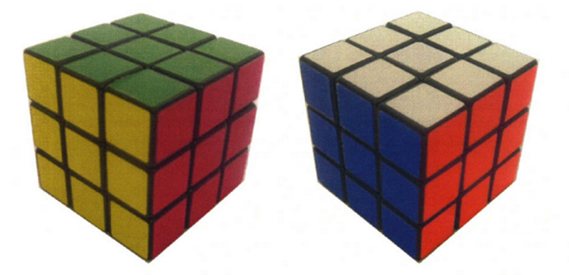

EU Trademark No. 5696232

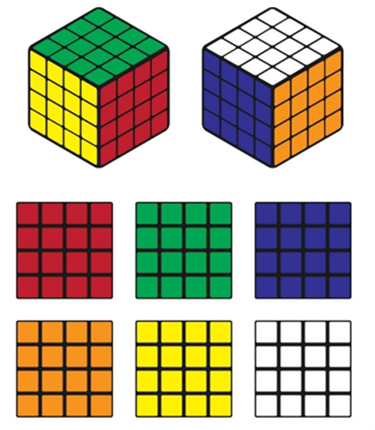

EU Trademark No. 9976135

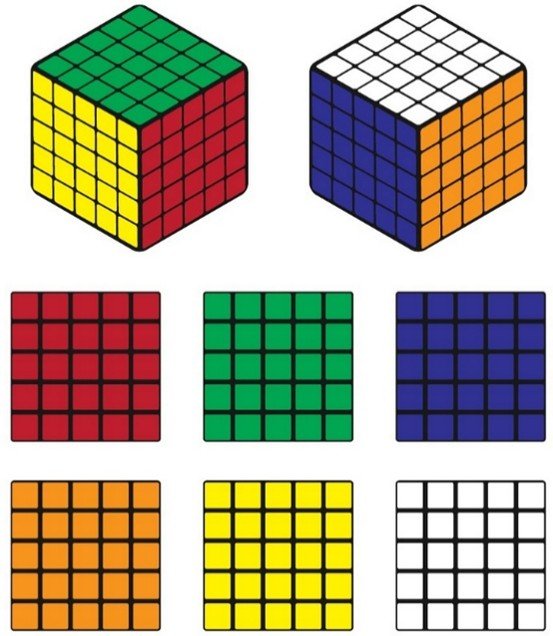

EU Tradmark No. 9976788

The dispute originated from applications for a declaration of invalidity filed by Verdes Innovations SA against the three-dimensional trademarks relating to the well-known cube.

The decisions of the Cancellation Division - which declared the marks invalid with respect to goods in Class 28 of the Nice Classification - were subsequently upheld by the First Board of Appeal of EUIPO.

Spin Master Toys UK Ltd brought actions before the General Court of the European Union against those decisions, challenging the declaration of invalidity based on Article 7(1)(e)(ii) of Regulation No 40/94 (now substantially reproduced in Article 7 of Regulation (EU) 2017/1001), on the ground that the sign allegedly consisted exclusively of the shape of the product necessary to obtain a technical result.

In all cases, the actions were based on a single plea in law, divided into three identical parts, alleging infringement of Article 7(1)(e)(ii) of Regulation No 40/94, read in conjunction with Article 51(1)(a) of the same Regulation.

First, Spin Master alleged an error of assessment in identifying the essential characteristics of the contested mark; second, an error in assessing the functionality of that mark; and third, an error of assessment relating to “puzzles”.

In essence, the applicant argued that the contested three-dimensional mark contained essential characteristics - in particular the combination of six specific colours and their arrangement on the faces of the cube - which did not consist merely of the shape of the product and which, in any event, were not necessary to obtain a technical result.

The decision

The four judgments revolve around the application of the absolute ground for refusal laid down in Article 7(1)(e)(ii) of Regulation No 40/94, which excludes from registration signs consisting exclusively of the shape of the product necessary to obtain a technical result.

In the case of the marks at issue, the cubic shape, the subdivision into smaller elements by means of a grid, and the chromatic differentiation of the faces were not regarded as arbitrary aesthetic choices, but rather as elements necessary for the functioning of the puzzle itself.

In order to solve the puzzle, it is necessary to distinguish the faces by means of different colours and to rotate the parts thanks to the modular structure of the cube: the configuration claimed essentially coincides with the technical mechanism of the game. The sign therefore does not merely “represent” the product, but incorporates its technical solution.

In all the decisions under review, the General Court rejected the argument that the Board of Appeal had erred in identifying the essential characteristics of the signs. No relevance was attributed to the specific combination of the six colours as such, but rather to the fact that the cubes are differentiated by means of colours capable of creating visual contrast between the faces. That differentiation was classified as a functional element, since it allows the identification of the faces and makes it possible to achieve the intended technical result

With regard to the second limb of the plea, Spin Master argued that the Board of Appeal had wrongly classified the essential characteristics of the sign as functional, on the ground that the colour combination and the grid structure of the cube were not strictly necessary to obtain the technical result, since that result could be achieved through different configurations.

The General Court rejected that argument, referring to settled case-law according to which a shape is excluded from registration where all its essential characteristics are necessary to obtain a technical result. The possible existence of alternative shapes, or the possible reputation of the sign, is irrelevant: what matters is that the shape, in its essential configuration, incorporates technical solutions which may not be removed from the free availability of competitors through the instrument of trademark protection. Otherwise, the proprietor would be granted a potentially unlimited monopoly over a technical result which the legal system intends to keep free once patent protection has expired - or in the absence thereof.

As regards the third limb, relating to the concept of “puzzle”, Spin Master argued that the Board of Appeal had attributed an excessively broad scope to that category of goods, treating as functional characteristics which, in its view, would not be intrinsically necessary to any three-dimensional puzzle.

That argument was likewise rejected. The General Court held that, with regard to three-dimensional puzzles of the type at issue, the modular structure of the cube and the chromatic differentiation of the faces constitute components intrinsically linked to the technical result pursued, namely the possibility of combining and recombining the elements until the solution is achieved.

Particularly significant is also the rejection of the argument that the absence of colour claims in patents historically connected to the Cube would exclude the functional relevance of colours. On this point, the General Court reiterated the distinct logic governing trademark law and patent law: for the purposes of Article 7, what matters is not the content of a previous patent protection, but whether the shape of the sign, as represented and described, displays essential characteristics necessary to achieve a technical result.

In conclusion, in all four cases the General Court confirmed the functional nature of the shapes claimed and, consequently, the invalidity of the trademarks. The judgments form part of a strict line of authority aimed at preventing trademark law from being used to obtain potentially unlimited protection over technical solutions which the legal system intends to keep freely available on the market.